Urban violence and child maltreatment are pressing concerns in Alabama. In 2021, the state investigated 26,116 reports of child abuse or neglect, underscoring widespread exposure to trauma (Associated Press, 2024).

Magnitude of the Problem

Nationally, about 60% of children are exposed to violence each year, and nearly 40% endure two or more violent acts (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention [OJJDP], 2009). In Alabama, child abuse and neglect rank as the state’s ninth leading health indicator (Alabama Department of Public Health [ADPH], 2020). Reports of maltreatment rose from 8,466 in 2015 to 12,158 in 2018, reflecting a concerning upward trend (ADPH, 2024).

How Violence Impacts Alabama Families

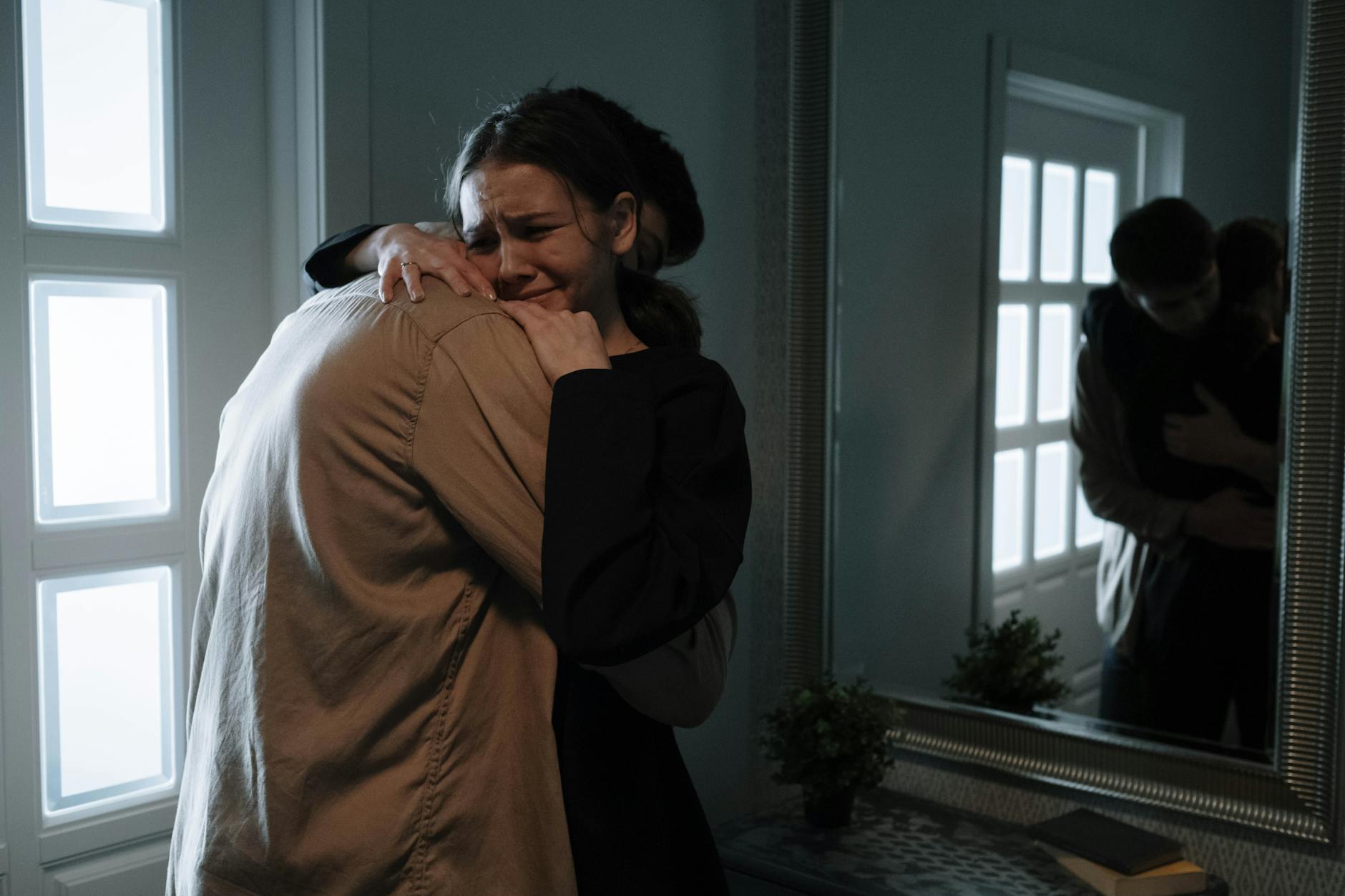

Children exposed to violence are at increased risk of anxiety, depression, behavioral problems, and poor academic performance (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024a). In Alabama, repeated exposure to maltreatment contributes to cycles of trauma that strain family health and community well-being (Associated Press, 2024).

How Schools Can Lead Change

1. Create Safe, Trauma-Informed Environments

Schools provide stability through predictable routines, supportive staff, and safe spaces—protective factors that buffer children from the adverse effects of violence (CDC, 2024a).

2. Expand Access to Mental Health and Family Support

Nearly 1 in 5 children exposed to violence show symptoms of PTSD (OJJDP, 2009). Schools can expand access to counselors and social workers, host workshops on coping strategies, and connect caregivers with trauma-informed parenting resources.

3. Strengthen School-Family Partnerships

Parent engagement nights and awareness campaigns help families recognize and respond to signs of child maltreatment (Associated Press, 2024).

4. Build Local and Justice Partnerships

The DOJ highlights that preventing youth violence requires collaboration among schools, law enforcement, and community organizations (OJJDP, 2009). Alabama schools can partner with child protective services and community centers to provide wraparound support.

Conclusion

With rising child maltreatment reports and community violence risks, Alabama schools serve as anchors of hope. By creating safe spaces, expanding services, and working alongside families and justice partners, schools can lead families toward resilience—even in violent urban neighborhoods.

References

Alabama Department of Public Health. (2020). State health assessment: Health indicator 9—Child abuse and neglect. https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/healthrankings/assets/2020_sha_health_indicator_9.pdf

Alabama Department of Public Health. (2024). Child abuse and neglect. https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/healthrankings/child-abuse-and-neglect.html

Associated Press. (2024, April 16). Alabama investigated 26,116 reports of child abuse or neglect in 2021. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/ebdd321ec237298c9972b042e55ff303

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). About community violence. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/community-violence/about/index.html

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2009). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey. U.S. Department of Justice. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/program/programs/cev